Spaceships travelling at many times the speed of light; humanoids meeting, greeting, shooting and loving other beings, their tentacles and eye-stalks swaying in the breeze; characters with unpronounceable names speaking wistfully in the midnight brightness of twin moons; these are just some of the ridiculous scenarios I’ve always scoffed at in science fiction. (I’ve always preferred earth-bound nightmares about the future.) Nonetheless, I’ve just read three of Iain M. Banks’ Culture novels – which are full of this sort of thing – back-to-back and this post will try to explain why.

Above all, there’s the Culture. It’s a vision of Utopia: every familiar problem has been solved through the magic of highly advanced technology. Everyone is equally “rich” in a civilisation that is so prosperous that there’s no need to divide resources. No one needs to work, although people often choose to, in professions such as artists, researchers, architects or spies, because those jobs are fun. The ones who don’t work live it up in giant space cities, or cruise around the universe or relax in the climate-controlled countryside of “Orbitals”, spinning habitats with low population density. Good health and longevity (or even immortality)can be taken for granted. People have evolved drug glands to control their emotions and sensations at any moment. They can even change sex, if they feel like it, in a process as straightforward as using an app.

There is no “but”. The Culture really is a wonderful place to live (apart from the danger of blandness, like the perfection of Sweden). It’s all in the hands of the “Minds” – artificial intelligences that are far beyond any biological ones. Luckily, they care for the well-being of all sentient creatures and will go out of their way to prevent discomfort to a single one. Very reluctantly, they will go to war with inferior civilisations, but only having carefully calculated that the benefits in terms of net happiness in the universe will outweigh the losses.

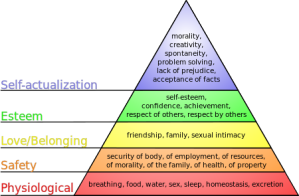

What is the value of such a Utopia, as removed as it is from our imperfect world? For one, it’s a secular technophilic vision of heaven. It’s based on something that currently doesn’t exist – the state of post-scarcity – so it can sidestep the problems (such as human nature and “corporate nature”) that make socialism and consumerism so far from perfect. It’s good to dream, to have something to hold up as an alternative to the blatant dystopia of Facebook as well as other older, more demanding ideologies. The values that the Culture stand for amount to ‘well-being’ all the way up the Maslow hierarchy of needs , or as Banks put it: “the things that really mattered in life, such as sport, games, romance, studying dead languages, barbarian societies and impossible problems, and climbing high mountains without the aid of a safety harness.”

The Culture also helps to put our current state of civilisation into perspective, by commenting on other more alien ones. In “Consider Phlebas”, the Indirans are at war with the Culture; in “The Player of Games”, the Culture is ready to take over the Azad and in “Excession”, the Affront try their luck. In each case, the alien race is hopelessly outgunned and condescended to by the involved Culture Minds and citizens as fundamentally more primitive in outlook. The Indirans are religious zealots, the Azad are intricately organised but ultimately caste-bound, the Affront are sadistic to the bone. It’s easy to sympathise with the Culture’s point of view and look down at these familiar foibles, just as we might look at the warrior Klingons in Star Trek. The vertigo only hits when we realise that these “inferior” civilisations are still in fact vastly superior to our own… because they have achieved the sort of political organisation that can harness the resources to master interstellar space flight.

The most interesting effect of the Culture is that it lowers the stakes. Because of its impervious position of technological superiority, nothing can hurt it. Apart from the artifact in “Excession”, the fate of the universe / galaxy / planet is never really at stake, because the Culture always wins. In “Consider Phlebas”, the action of the plot will only affect the projected end date of the war, not its outcome. In “The Player of Games”, the plot only decides to what extent the Azad will be demoralised before the Culture moves in to civilise them. In “Excession”, the plot concerns whether or not the Culture should go to war against the Affront, without any doubt about the eventual victory. So what’s the point?

Lowering the stakes returns the focus to individuals, the level at which any book allows us to relate. I don’t care about the answer to “Do androids dream of electric sheep?” because I don’t know any androids. Likewise, the fate of the galaxy is a difficult thing to relate to when even a city contains multitudes beyond our apprehension. In the Culture novels, despite all the impossibilities of the technology, the incomprehensibly vast distances covered, the exotic cityscapes, the explosions that Hollywood still can’t budget for and the many-limbed creatures, the action centres on people meeting each other in rooms and resolving their differences.

The distinction in the Culture novels from the usual Earth-centred fiction that we read and Earth-centred lives that we lead becomes the constant awareness of the immense volumes of deep space that surround the characters, whether they are speeding between galaxies or lounging in a villa on a rotating Orbital. But there’s the rub. That deep space surrounds us too, as we spiral through the void on a planet that becomes a blue marble then a point of light then nothing at all without zooming out all that far on the cosmic scale.

The view of space that the Culture novels provide us with isn’t escapism but a reminder of our place in the universe- roughly nowhere. So let’s enjoy ourselves while we’re here. Thanks for that Iain M. Banks. R.I.P.

Now that I’ve seen beyond the horizon, would you recommend any other space-faring stories?

After shunning it for years, I’m finally getting into the series myself. The perspective proffered here is new to me, though.

I think there’s an aspect of Iain Banks’ writing that is easy to dislike, in both his science fiction and “serious” books. There’s an awareness of Banks attempting to depict something, whether it’s a huge setpiece in the Culture books or some twisted scenario in the other books, and it’s easy to find his work unconvincing because of that awareness. As a young wannabe writer, I imagined I could do better. Years later, I obviously still haven’t and I’ve come to appreciate Banks’ ability to follow up on the promptings of his imagination, despite the occasional bit of clunkiness in the narratives.

Regarding Iain M. Banks’ novels and the Culture as a sort of “computer-aided” anarchy, there is also this academic article:

Yannick Rumpala, Artificial intelligences and political organization: an exploration based on the science fiction work of Iain M. Banks, Technology in Society, Volume 34, Issue 1, 2012, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160791X11000728

(Free older version available at: http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/rumpalaepaper.pdf )

Thanks, Yoda. It would be pretty cool to bridge the gap between the present day and a Culture-style future.